BOOK REVIEW: ‘Catching Fire’ by Richard Wrangham

Have you ever wondered about this… No other species cooks, except us humans! The closest that any other species gets to cooking are chimpanzees. They apparently mix (any) mature leaves with meat in order to make it more ‘chewable’. Since the leaves give traction to their teeth, this helps in grinding down the meat faster… that’s it. And all other species consume their food unprocessed.

Why then do we humans cook? We use dozens of techniques to make our food softer, finer, crunchier, aerated, juicier. We break ingredients down with heat, with force, with acids. We manipulate them to ‘improve’ taste, texture, aroma, flavour, visual appeal, mouthfeel… Is all this necessary? Is there an evolutionary reason for why we cook?

Yes, thinks RIchard Wrangham, an acclaimed anthropologist and primatologist who taught Biological Anthropology at Harvard. His book “Catching Fire – How Cooking Made Us Human’ is a mind blowing, research-backed account of how cooking may have played a major role in our very evolution into homosapiens.

The Core Idea

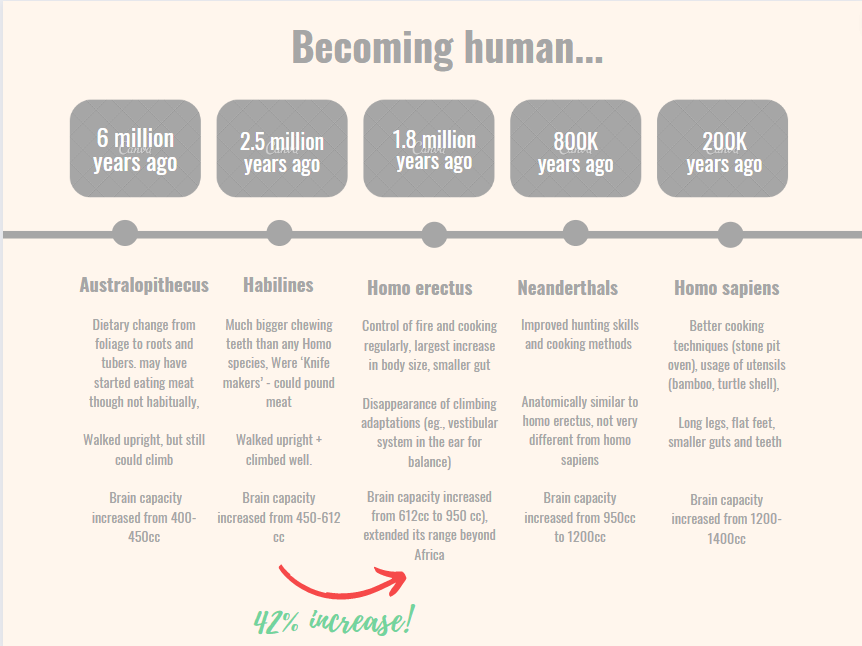

In short, the book outlines the evolution of the human species – right from our ape ancestors up to present day homo sapiens – from the lens of their eating habits and the bodily adaptations that resulted from these habits. Here’s a chart I made to capture the crux of this evolutionary journey:

The jump in cranial capacity (brain size) from habilines to homo erectus is a whopping 42%!

The key question that this book attempts to answer is “What explains the significant jump in brain size from habilines to homo erectus?”. With convincing and clear analysis, Wrangham explains how this huge jump is likely to have been a result of a switch to regularly cooking the food we ate.

Things I like about the book

- Despite straddling topics from multiple fields (archaeology, history, biology, sociology, nutrition, etc) and sharing results of research studies, the book is very accessible and easy to read

- I love that Wrangham not just shares results, but takes us through the scientific enquiry process as well – For eg., while pondering the potential reasons why the biggest brain capacity increase from habilines to homo erectus may have happened, he explores multiple hypotheses. Then narrows down on the cooking hypothesis. He also explains the drawback of this hypothesis (archaeological evidence for the earliest instances of cooking is not reliable and why so). And how he uses an alternative approach (using anatomical evidence) that is more reliable.

- He not just covers the core idea and the evidence for it. Some chapters are devoted to exploring the downstream impacts too – eg., advantages and disadvantages of our bodies’ adaptation to cooked food, sociological aspects like how sharing and cooperation may have started, how sexual division of labour could have been brought about by cooking, etc

- He also delves into practical questions and covers topics that are relevant for humans today – e.g., how we get more nutritional value from cooked foods compared to raw foods, why this happens (ie, what happens during cooking of starch, proteins and fat), how nutritional value is measured in the lab (the Atwater convention used for calculating the nutritional labels provided on packaged food); how our body assimilates nutrition from food and how this is very different from lab measurements; what are the complexities in estimating how much nutrition would be absorbed from a given dish by a person with certain attributes, etc

- Throughout the book, Wrangham provides fascinating anecdotes, descriptions and results of multiple studies, species, peoples, eras and cultures from around the world. Reading it felt like being on a trip through time and space!

The WHY WHY score

I would rate the book 9.5/10. It is a must-read if you are interested in knowing the reasons behind why we do what we do in the kitchen. More interestingly, it provides a meta-perspective on why we cook at all!

interesting tidbits from the book

- If it were not for cooking, we would be spending ~42% of our waking time chewing!

- The maximum limit for safe protein intake is ~50% of our calories. The rest of the calories MUST come from fat and carbohydrates. Else, excessive protein intake beyond this limit leads to a form of poisoning!

- Fatter people spend less energy than leaner people to digest the same food… uh oh!