Should you mix idli batter with your hands?

Ok, so you have soaked and ground rice and urad dal separately. Now how do you mix the two batters together to get the spongiest idlis? With a ladle? With a whisk? With your hand? In the wet grinder itself? Does the mixing method make any difference at all?

The hand-mixing theories:

My mother and my mother-in-law always mix the batters with their hand and they strongly recommend it. They say that our hands are home to some useful microbes which help with fermentation. Many online homecooks too recommend hand-mixing in their blogs and videos. Apart from the ‘useful-microbes-on-the-hand’ theory, they also say that that our body temperature adds additional warmth to the batter, raising its temperature and thus, accelerating the fermentation rate.

I had questions about both these theories. The difference between room temperature (say ~25deg C) and the body temperature (37deg C) is not much. And we hardly spend 3-4 minutes mixing the batters which typically weigh 2-3kg at home-scale use. So, surely hand mixing will not affect the batter’s temperature too much? (I haven’t yet found a simple method to estimate the increase in temperature. If you happen to know, please leave a comment! Meanwhile, I’m also thinking of finding it experimentally).

As for the useful microbes theory, Doc.Dough’s post in thefreshloaf articulates my doubt really well: “If your hands are clean enough to put into the batter, they don’t have anywhere near enough bacteria to impact the fermentation, and if your hands have enough bacteria on them to make a difference, then you don’t want to put them into a batter that may encourage the propagation of contaminants.” Do you agree?

This is a valid concern since more than 150 species of bacteria are found on an average on any person’s hand. These bacteria thrive at a density of about 107 cells per square centimetre of your skin! And only about 3% of this is Lactobacillus (the kind of bacteria that help with safe fermentation of idli batter). So, is it actually safe to mix batter with your hands? Won’t these other bacteria interfere with the fermentation? Does mixing with hand actually make a difference? Or is it just a myth passed on through generations of home cooks?

The initial-aeration theory:

Adding to my doubts on this, I also came across this statement about leavening (gas production) in Harvard University’s Science and Cooking course materials: “Baking yeasts and chemical leavenings are routinely used to fill baked goods with gas bubbles. A common misconception is that these products create new bubbles: in fact, the carbon dioxide in yeast is released into the water phase of the batter, diffuses to the pre-existing air bubbles and enlarges them. This is why the initial aeration of dough and batter through kneading, strongly influences the final texture of baked goods..” Is this true for natural fermentation by lactic acid bacteria as well? If yes, is the initial aeration by the wet grinder (when it foams up urad batter) sufficient? Or can we introduce some extra aeration by using a whisk to mix urad and rice batters?

The convenience theory!

Why go to such lengths when you can just let the grinder do the mixing job? You can simply add the urad batter back to the grinder after it has finished grinding the rice, right? And the grinder will do a more efficient job mixing the two thoroughly. But does grinder-mixing add more aeration while mixing the two batters? Or does it deflate the urad batter that it had helped fluff up earlier?

Anyways, the grinder-mixing option is the least-messy and the most convenient one. It does not involve using another big vessel to do the mixing. No messing your hands either. You can simply pour-off the mixed batter into your fermentation container. So, I always used this option as my default.

Until curiosity got the better of me 🙂

Testing four mixing methods:

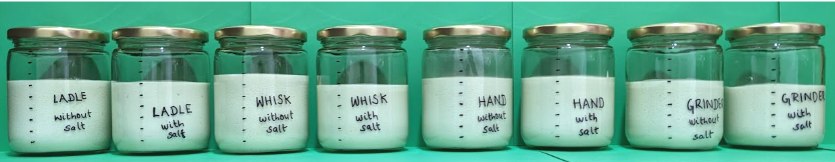

To test which mixing method gives the best results, I divided a big batch of urad and rice batters into 8 parts. This is because I wanted to test four mixing methods – using a ladle, using a whisk, mixing by hand and letting the grinder do the mixing. (For each method, I did a salted version and an unsalted version since I was also running an experiment on the effect of adding salt before and after fermentation. More on that in my next post on when to salt idli batter.)

For each sample, I mixed exactly the same amounts of urad and rice batters for the same amount of time (1 minute):

Here are the mixed batters before fermentation, poured into glass jars so we can see the differences well:

Each marking on the jars is 50ml. Notice how the whisk-mixed samples seem to have a higher volume. I think this is because the whisk introduced additional aeration of the batter while mixing.

Also see how the grinder-mixed samples are much lower in volume. There could be two reasons for this – the urad batter got deflated while mixing. Plus, some of the batter stuck to the grinder itself. Because these are small samples, the % difference in volume is significant though the amount of batter stuck to the grinder was small.

Which method showed the maximum rise during fermentation?

Here are the samples after 19 hours of fermentation:

The unsalted samples have all risen more than the salted ones. But this is not actually an advantage, as you can read from my separate post on when to salt idli batter.

For now, consider the salted samples alone. It looks like the sample mixed with hand indeed has the highest volume compared to the other methods. Does this increase in volume indicate faster or better fermentation? Is it really true that our hands have useful microbes that affect the fermentation? I’m not sure of the answer to the first question. But look at what I found when I searched more about the influence of microbes found on the hands of cooks!

What research Says on the hand-mixing theory:

Just like naturally fermented idli batters, sourdough starters are also have naturally occurring microbial communities. In 2020, a group of researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Madison studied the influences of ingredients and bakers on the bacteria and fungi in sourdough starters and bread. In this study, 18 bakers from two continents used the same recipe and ingredients from the same source/batch to make starters (in their own home country) that were then baked into breads.

It was found that the microbial community in the starters mainly came from the bread flour (including species of microorganisms that lived inside the grain (endophytes) and those species found living on the outside of the grain). But the diversity of microbes found in the starters was also associated with differences in the microbial community on the hands of the bakers! “A relatively large number of bacterial and yeast taxa were shared between the skin microbiome on bakers’ hands and the sourdough starters but were not found in the flour. We suspect that these taxa colonized the starters from hands”. So it does look like there is proven evidence for microbes on the cook’s hands playing a significant part in impacting the dish.

Interestingly, the bacterial composition varies quite a lot from person to person and also, from one hand to the other, in the same person! “Hands from the same individual shared only 17% of their phylotypes, with different individuals sharing only 13%”. So, the mix of microbes in each person’s hand is unique (and it varies over time as well).

So, if you have ever felt that the idlis that your mother made were uniquely tasty and that nobody can replicate that taste, you were right!

My takeaways:

From the research above and based on my trial comparing different mixing methods, I do think that hand-mixing has a real impact on the fermentation of idli batter. My hypothesis is that it helps by adding a significant proportion of Lactobacillus to the batter. At a density of about 107 cells of bacteria per square centimetre of your skin, even if only 3% of this is Lactobacillus, their numbers would be the same order of magnitude as the number of useful bacteria (L.mesenteroides and E.faecalis) found after 8 hours of soaking urad dal (Refer to my earlier post sharing numbers on the growth of these useful bacteria over different soaking durations).

So, when we mix the batter with our hand, this probably adds a significant number of helpful bacteria to the batter. This increase in its numbers probably gives the right species a headstart in colonising the batter early on. The higher numbers probably also help produce more carbon-di-oxide compared to the other methods, hence yielding the highest volume.

But what I also found from my other experiments is that very high volumes in the fermented idli batter is not always an advantage. If too much gas is produced, it forms very big bubbles and the gas escapes when you stir the batter before steaming. If you don’t stir the batter before steaming, this additional gas causes the idlis to puff up initially while steaming, but their amount is too much for the batter to hold. So gas escapes in big chunks and the idlis then show cracks on top or deflate and flatten soon after.

So, I would suggest that you mix idli batter with your hands only if you think there are other reasons why your batter might not ferment or foam well. For example, if you live in a cold place, if your urad has not fluffed up well, your urad dal is from an old batch, the batter consistency is slightly thick and you worry that the idlis might turn out dense, etc.

Regarding the safety aspect – I have never come across any cases of food poisoning or other problems from freshly-made idlis, maybe because they are steamed. I’m also biased by my personal experience seeing cooks in my family regularly mix the batter with their hands. No untoward incidents have resulted from that yet, so I assume it is quite safe to mix idli batter with clean hands. Just take care that the idlis are thoroughly cooked through and served fresh.

Bonus: Fun facts about microbes on the hands of cooks::

- While humans contribute microorganisms to the starters/batters, the reverse also appears to be true! This was a surprise finding from the same study quoted above: “While our study was not designed to test this explicitly, it does indicate the extent to which the skin microbiomes of bakers’ hands are unusual relative to the hands of non bakers.”

- Lactobacillus tend to be more common on the hands of women than those of men. Specifically, Lactobacillaceae were found to be 340% more abundant on women compared to men. 2% of the bacteria on the hands of men and 6% of those on the hands of women were from the Lactobacillaceae family. The higher amounts of Lactobacillaceae in women is thought likely due to incidental transfer of vaginal bacteria (human vaginal communities are dominated by Lactobacillus species). Also, interestingly, the palms of women were also found to harbour significantly greater bacterial diversity than those of men!

What do you think of that?

References:

- Reese AT, Madden AA, Joossens M, Lacaze G, Dunn RR. Influences of Ingredients and Bakers on the Bacteria and Fungi in Sourdough Starters and Bread. mSphere. 2020 Jan 15;5(1):e00950-19. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00950-19. PMID: 31941818; PMCID: PMC6968659.

- Fierer N, Hamady M, Lauber CL, Knight R. The influence of sex, handedness, and washing on the diversity of hand surface bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Nov 18;105(46):17994-9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807920105. Epub 2008 Nov 12. PMID: 19004758; PMCID: PMC2584711.