Why do we add fenugreek seeds to idli batter?

Fenugreek seeds evoke strong reactions. Some cooks never add it to their idlis while some don’t make idlis without them. I fall in the second camp, mainly for the divine aroma you get when you make dosas with the same batter. But I never knew what role fenugreek seeds play in the case of idlis.

I asked experienced cooks in my family, checked out popular food recipe blogs and went through publicly-available research to find the reasons attributed to the addition of fenugreek seeds. Then I proceeded to test a few of these hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: They accelerate the rate of fermentation

Some cooks say that fenugreek seeds are added to rice while soaking, since rice does not have starter microbes like urad dal and fenugreek seeds do. And so the fenugreek will help accelerate the fermentation. If that were the case, the more fenugreek you add, the faster should be the rate of fermentation, right? To test this, I divided a batch of idli batter into 4 equal samples (150 gm each). Next I prepared a paste mixing fenugreek seed powder in a few teaspoons of water.

The mixture turned thicker over about an hour, so I added a few more teaspoons of water to thin it out. (The colour difference is because it had started getting dark into the evening).

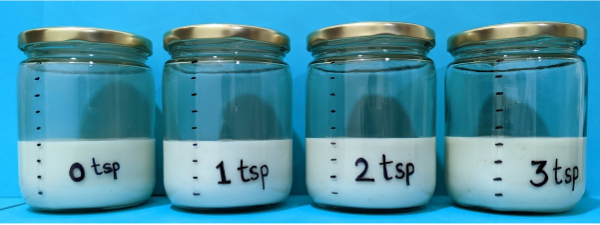

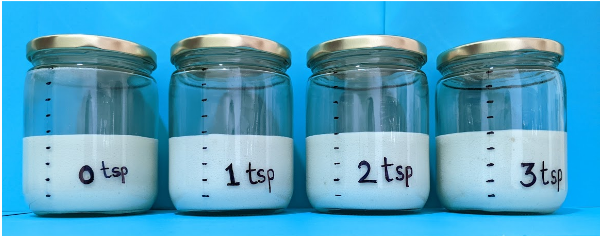

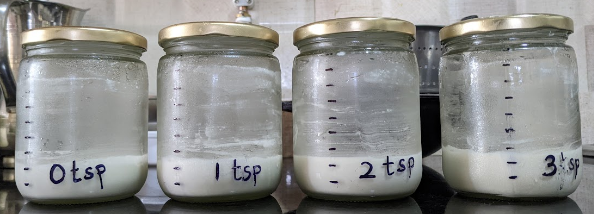

I added 0 tsp (no addition), 1 tsp, 2 tsp, 3 tsp of this fenugreek seed paste to the 4 samples of idli batter:

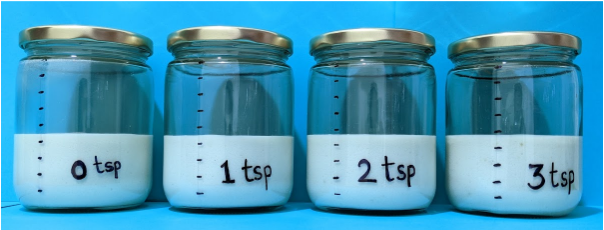

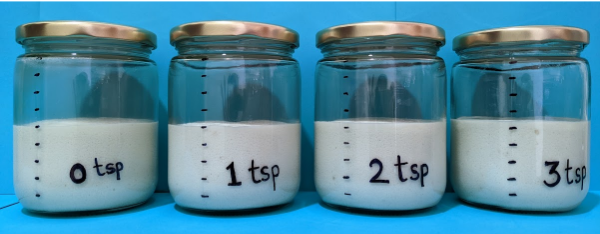

Then I set them out to ferment. Here is how they turned out:

Before fermentation:

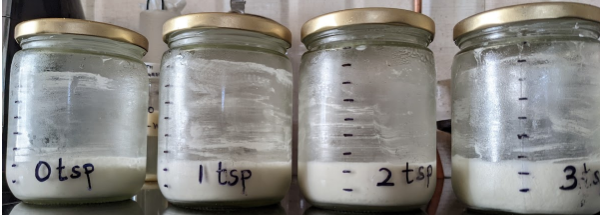

At 9 hrs of fermentation:

At 10 hours:

At 11 hours:

At 12 hours:

At 13 hours:

At 14 hours:

At 15 hours:

There weren’t any visible changes after this. So, long story short – I could not find any drastic differences in the volume or in the rate of visible changes that occur during fermentation, irrespective of how much fenugreek seed paste was added. Of course, there could be other differences that are not visible to the eye. But from a home cook’s point of view, there doesn’t seem to be much of a noticeable difference.

Hypothesis 2: Fenugreek increases the viscosity of the batter and helps in trapping gas, yielding spongier idlis

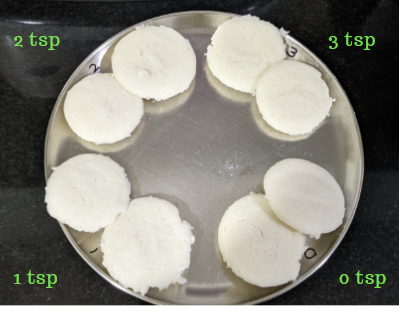

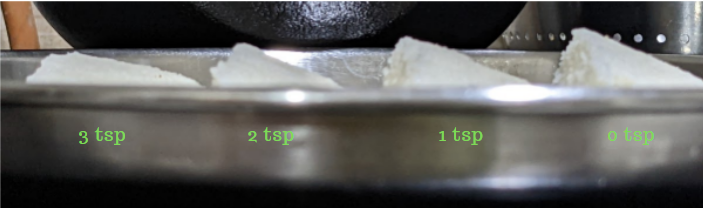

To check if this was true, I steamed 2 tbsp of each of the samples and compared the idlis for differences in their taste and texture. Here are the steamed idlis:

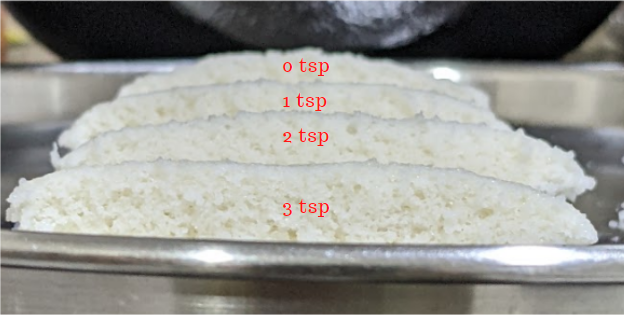

The differences are better seen when they are cut in half and observed sideways:

So, the more fenugreek paste added, the flatter the idlis. This is very similar to the effect of having a higher urad dal (black gram) proportion in the batter! Looks like a teaspoon of fenugreek paste behaves like an additional quarter cup of urad dal added in the recipe. (And this gave birth to my 5th hypothesis). But the level of sponginess was not detectably different when we tasted the idlis.

Hypothesis 3: Fenugreek gum is a good stabiliser and so delays batter separation

It has been found that fenugreek seeds have a polysaccharide (carbohydrate) called galactomannan, which behaves very similar to the arabinogalactan in urad dal. (My previous post on reasons why we use urad dal and not any other pulses for making idlis explains about surface activity and its role in trapping air and maintaining the foam). It has been found that fenugreek gum has superior surface activity compared to other similar gums (like guar gum, locust bean gum, etc) due to the specific structure of galactomannan in it. As a result, fenugreek gum is supposed to stabilise both oil-in-water emulsions and air-in-water foams (like the idli batter) with a longer effect.

Because of this stabilising property, fenugreek gum is now extensively used in the food industry as a stabiliser in ice cream, chocolates, etc. (In case you are wondering about the strong flavour and smell – while whole raw fenugreek seeds are bitter and pungent, the gum extracted from the seeds is supposedly tasteless and odourless!)

I tried to check if this emulsification property is exhibited by fenugreek seed powder as well – by mixing oil and water in two bottles, one with fenugreek seed powder and the other without. Initially, there wasn’t much difference between the two separation times:

But when the powder was left to soak in for a few more hours, the oil turned into some kind of thick gel. And the mixture showed considerable delay before the oil and water separated:

The more the fenugreek soaked, the longer the separation time. To check this delayed separation effect in the case of idli batter, after steaming the test idlis (shown above), I left out the samples in the fridge and checked them from time to time.

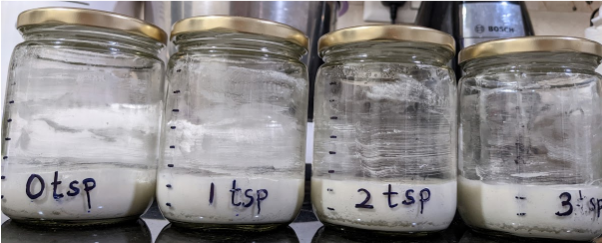

I did not notice any difference in 36 hours:

After 60 hours, only the sample with 2 tsp fenugreek paste showed slight signs of separation:

After 72 hours, all the samples showed similar levels of separation:

(Check out the bottom of the jar for the separated film of water. For the 0tsp sample, the film was visible more clearly on the other unlabelled side of the jar)

So, while current research says that addition of more fenugreek should have resulted in prolonged batter stability, I did not find that to be the case in my trial. Am I missing something here? Should I have done the experiment differently?

Hypothesis 4: Fenugreek seeds yield plenty of nutrition and health benefits

Fenugreek seeds are commonly used as a home-remedy staple in India, particularly for addressing digestion-related issues. Whether to ‘reduce body heat’ in summer by adding fenugreek seed powder to buttermilk or to reduce menstrual cramps by simply swallowing a couple of teaspoons of the seeds with water, they featured regularly in my grandmother’s suggested home remedies.

On searching for proven research around their medicinal use, I was overwhelmed with the range of health benefits attributed to regular consumption of fenugreek seeds. Including some of these here:

- Fenugreek has strong pain-relieving and appetite-stimulating potential.

- Fenugreek seeds are a rich source of fiber (50–65 g/100 g) mainly composed of non-starch polysaccharides like galactomannan. These polysaccharides increase the bulk of the food and facilitate bowel movement and assist in smooth digestion.

- Fenugreek fibre is capable of moderating human glucose metabolism. It helps to lower blood glucose absorption, controls sugar level, and thus facilitates insulin action. (Meghwal and Goswami, 2012).

- When fenugreek fibre-fortified flour was used for making snacks fried in oil, they absorbed 8–15% less oil (Im and Maliakel, 2008).

- Moreover, mucilage, tannins, pectin and hemicellulose present in the seeds inhibit bile salt absorption in the colon and facilitate low density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL) reduction in blood.

- It binds the toxins of food and indirectly protects intestinal epithelial membrane from onset of cancer.

I am not an expert in this area and there is no way I can conclusively evaluate these claims. But these purported health benefits are another strong reason why many folks include fenugreek seeds in their regular diet in south India. Examples of how it is put into routine use are:

- as a main flavouring ingredient in curry powder

- in idli batter

- in gravies / kuzhambu which are paired with steamed rice

- as a key ingredient in seasoning / tempering / tadka / thalippu, etc.

Hypothesis 5: Cost savings, since fenugreek seeds reduce the amount of urad dal needed

From the testing of hypothesis #2 above, it appears that fenugreek acts like a stronger substitute for the properties that urad dal brings to the idli recipe. Each teaspoon of fenugreek powder added replaces about a quarter cup of urad dal. Hence I think fenugreek may also hav e been looked at as a cheaper substitute for urad dal, while also including the health benefits mentioned above.

How much cost savings does this mean?

Consider a batch of idli batter made with 6 cups of idli rice (~1000gm) and 1.5 cups (~270 gm) of urad gota, the whole deskinned version of urad dal. The approximate cost of ingredients in today’s bigbasket rates (the ‘BB Royal’ versions, for better quality ingredients) would be Rs. 46 for rice and Rs. 40 for the dal. Total Rs. 86.

If you were to replace half a cup of urad dal with 2 tsp (10 grams) of fenugreek, the cost would be Rs. 46 for rice (1 kg), Rs 26.5 for the 1 cup of urad gota (180gm) and Rs. 2 for the fenugreek seeds (10gm). So, total of Rs 74.5.

This is a saving of Rs. 11.5 from the original Rs. 86 and amounts to about 13.4%. This savings is not insignificant, particularly for large scale operations like someone running a commercial idli batter business. At that scale, % savings could be different since the rate at which they purchase rice and dal would be lesser. But in any case, it is true that addition of fenugreek seeds in the idli recipe would bring down the total cost of ingredients.

Hypothesis 6: Fenugreek seeds add flavour to the idlis when steamed

This is my favourite hypothesis and I’m clearly biased 🙂. I always add fenugreek seeds while making idli batter. And I’m not the only one in my family. My 8-year old son does not touch idlis made without fenugreek seeds 😀 And I simply cannot resist their roasted aroma when we make dosas with the batter.

For their tiny size, the seeds pack quite a punch of flavour and aroma. Even though we add just tiny amounts in most recipes (in the case of idli, just a teaspoon for 4 cups of other ingredients), their flavour comes through quite powerfully. The principal flavour component behind their strong mushroom-like, roasty, pungent, buttery and spicy flavour is called Sotolone (3-Hydroxy-4,5-dimethyl-2(5H)-fbranone – for those who are interested 🙂 .

The reason why even a little bit of it goes a long way is that the typical concentration range of sotolone in fenugreek seeds is about 3-12 mg/kg. This is at least 3000 times higher than the threshold at which we can detect its presence! (The actual amount of sotolone in the seeds depends on the geographical origin ie., where the seeds are grown. For eg., fenugreek seeds from Egypt are supposed to have a very intense flavour compared to the ones we get in India).

If you like the flavour of fenugreek seeds, you can try incorporating them in your chapati dough too. For every 500gm of wheat flour, dry roast 1 tsp fenugreek seeds until they are dark brown and 2 tsp flax seeds until they crackle. Cool the seeds and powder them coarsely. Add to the flour while kneading dough. Your rotis will turn out very fragrant!

Summing up

Based on all the hypotheses and my trials, I did not find conclusive evidence for its stabilising properties or ability to accelerate fermentation. I think that fenugreek is mainly added in the idli recipe for its flavour, its purported health benefits and its ability to substitute for urad dal more effectively. The cost factor is also a compelling reason why it could be widely used in commercial idli dosa batters.

Bonus – some fun facts about fenugreek:

- It is actually a legume (ie, belongs to the family of pulses)!

- The maple aroma and flavour of fenugreek seeds have led to its use in imitation maple syrup. If you consume the seeds or their extract, their flavour causes your urine and sweat to have a maple-like smell too!